Nicole D’Alessio — January 12, 2015

Increasing environmental awareness among consumers has led to strategies that brand environmental characteristics of products. This trend is observed with product labels such as “partial zero-emission vehicles” (PZEV), “Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design Buildings” (LEED) and “dolphin safe” tuna. Branding through labels is also used in the ornamental plant industry, such as Proven Winners® and Knock Out® roses. These examples demonstrate the use of labels to call attention to features that differentiate products. The use of branded labels can influence sale prices and/or market shares.

Growers of ornamental plants tend to think of themselves as price takers in markets, with prices driven by those offered in “big box” home and garden centers. This perception may arise because big box stores are the primary venue for retail nursery sales and because smaller retail outlets attempt to be price competitive. In addition to the market competition, the collapse of the U.S. housing market in the Great Recession placed further financial pressure on the nursery industry. From 2002 to 2007, the number of U.S. horticultural operations decreased by almost 15 percent, with a further reduction of 4 percent from 2007 to 2012. Sales in the industry as of 2012 had recovered to $14.7 billion, but was still $400 million lower than 2002 sales of $15.1 billion. Nurseries remaining in the industry are producing less and have become more cost efficient in managing their operations.

Growers are also faced with potential climate and regulatory stressors. For example, in July 2013, 46 percent of the contiguous United States was experiencing moderate to exceptional drought, which left many growers at significant risk of production losses. In addition, federal and state agencies in some areas are encouraging growers to capture water runoff from irrigation and storm events in order to reduce nonpoint source pollution and meet Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) targets for nearby water bodies. A TMDL is a target limit for pollutants reaching a specific water body. Specific examples are TMDL targets for nitrogen and phosphorus entering the Chesapeake Bay. The Maryland implementation, which calls for regulatory enforcement, has targeted statewide reductions in nitrogen and phosphorus loading from agricultural lands by 24 percent and 12 percent respectively by 2025. Best Management Practices will need to be employed to meet these targets. One such practice for nursery operations to reduce nutrient loading is through capturing irrigation and stormwater runoff, which can then be reused for irrigation and serve as an assurance supply of irrigation water in periods of drought.

Using recycled irrigation water and stormwater runoff from growing areas raises the possibility of re-inoculating plants with disease (for example, Pythium and Phytophthora). Initially, such diseases may only affect a small number of plants, but using recycled water in an irrigation system can spread the disease through the entire growing area. Such re-inoculation is a major concern for growers; results from a survey we conducted of Mid-Atlantic nursery growers indicates that 36 percent of growers typically lose plants worth more than 3 percent of their annual sales to disease.

A 2009 study of the Georgia ornamental industry suggests that approximately 7 percent of plants are lost to disease annually, with a reduction in crop value of roughly $40 million and approximately $22 million spent on control costs. Any requirement to capture water runoff will increase operating costs for growers to control the spread of plant diseases or will result in increased loss of plants with an associated loss of revenue.

Eco-labeling for profit?

Product labeling may provide a mechanism for growers to recoup at least some of the costs of changing the infrastructure of their operations to capture water runoff from growing areas and to control disease from subsequent reuse of water in irrigation systems. Labels indicating that ornamental plants were grown using water conservation practices and are disease free is one option. These labels could create niche markets for ornamental plants that would appeal to consumers’ environmental preferences and their desires to avoid purchasing diseased plants that might die after purchasing. The question is: Will consumers pay a premium price for eco-labeled horticulture products?

In addition to the Proven Winners® and Knock Out® rose labels mentioned, USDA Organic and private Veriflora® certifications already exist in the industry, which suggests that consumers are responding to plant labels. Several regional labeling programs also exist, including Texas Superstar™ and Earth-Kind, Oklahoma Proven, Nevada Grown and California All-Stars. These labels typically certify plant quality, that a plant is suited to the local climate, but do not emphasize plant production practices.

The USDA Organic Seal, which originated in 2002, is among the most recognized eco-labels. This seal certifies that growers utilize production methods that protect biodiversity and encourage the preservation of natural resources. Although the USDA Organic certification has been a popular option among agricultural producers, floriculture and bedding crops only comprise 6 percent of organic sales in the U.S.

Veriflora® certifies that ornamental plants are grown to specified standards of sustainability, such that production supports ecosystem preservation, natural resources are conserved, waste matter is properly disposed of and recycled, fair labor practices are employed, local communities are supported, and quality control systems are enacted.

Though attractive for growers looking to differentiate their products, both Veriflora® and USDA organic certifications can present costly barriers to entry into eco-labeled production for financially constrained growers. If growers are uncertain about the price and market share implications of labels, and changes in production practices to participate in the programs are costly with unknown implications for plant quality, growers may be hesitant to seek certification.

Photo: Rene Mansi / iStock

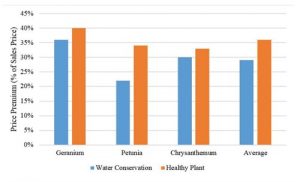

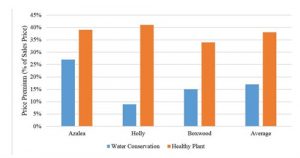

To help growers understand the potential price implications of eco-labeling ornamental plants, we conducted a study of retail purchasers of horticultural plants in Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia and Georgia. In 2012 we surveyed 1,596 individuals who had purchased ornamental plants within the preceding year. In the survey, we asked consumers if they would pay price premiums for three annual bedding plants (geraniums, petunias and chrysanthemums) and three perennial evergreen plants (azaleas, hollies and boxwoods) that had “Water Conservation” or “Disease Free” labels. By presenting people with purchasing options that varied by the prices of plants—and labels—and other plant features, we are able to estimate the price premiums people might pay for ornamental plants labeled water conservation or disease free.

The labels that were analyzed included the Water Conservation and Disease Free certification labels shown opposite. These certification labels were added to labels that might appear on a plant pot. The Disease Free label certifies the health of a purchased plant, while the Water Conservation label certifies that a plant was grown with water conservation practices. Three potential certifying authorities were considered in the survey: a governmental organization, an industry organization and a non-governmental organization.

The survey results indicate that consumers are willing to pay price premiums for water conservation and disease free labeled ornamental plants, and the premiums are not influenced by the certifying authority. Price premiums for annual bedding plants range from about 20 percent (petunia, Water Conservation label) to 40 percent (geranium, Disease Free label). The Disease Free price premiums are generally slightly larger than the Water Conservation premiums, which suggest that people may be somewhat more concerned with avoiding diseased plants than purchasing plants that are grown with water conservation techniques.

Annual Bedding Eco-Label Price Premiums

The concern for disease free plants is much more prominent for the broadleaf evergreens, with the price premiums being much higher than for water conservation. This pattern of results makes sense. Broadleaf evergreens are more expensive than annual bedding plants, take more effort to establish and are long-term investments in a homeowner’s residential landscaping, resulting in the likely perception of diseased plants posing a financial risk to homeowners. On the other hand, lower price premiums for water conservation may be a concern because it takes longer to grow broadleaf evergreens (years) and consequently more water may be used in the growing process.

Broadleaf Evergreen Eco-Label Price Premiums

This exploratory study strongly suggests that if growers adopt water recycling to ensure against drought or in response to government actions, it may be possible to recoup some expenses through higher sales prices for certified plants. Controlling disease and using a Disease Free label may be the key to obtaining price premiums for plants.

A few caveats should be considered in interpreting our results:

- First, the survey measured consumer purchase intentions, not actual purchase behavior. Thus actual, effective price premiums in stores might be less than reported here. Market trials are needed before the labels are actually implemented. The market trials can also investigate the best mechanism for portraying labels on plants.

- The price premiums are based on final sales to consumers at retail outlets. Growers who sell through rewholesalers or who wholesale their plants may not receive the full benefits of certification, depending on sales contract provisions.

- Our results do not provide insights for landscaping firms that purchase ornamental plants for landscaping at residential, retail and commercial properties. A stimulus for price premiums in this market may be to have LEED certification include “greenscaping” around new and retrofitted buildings.

- Product labels are gaining popularity in consumer markets to convey information to consumers and to create market niches. With nursery operations facing market, climate and regulatory risks related to water conservation and disease management, innovative approaches to enhance revenue are needed. Creating value for consumers through information provided on certified labels is a promising approach.

References

U.S. Department of Agriculture (May 2014). 2012 Census of Agriculture: United States Summary and State Data, Volume 1 Ge graphic Area Series Part 51. Retrieved Dec. 19, 2014, from http://www.agcensus.usda.gov/Publications/2012/Full_Report/Volume_ 1,_Chapter_1_US/usv1.pdf

U.S. National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center (July 2012). U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook. Retrieved from http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov, July 2012.

Maryland. Department of the Environment (October 2012). Maryland’s Phase II Watershed Implementation Plan for the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. Retrieved from http://www.mde.state.md.us/programs/Water/TMDL/TMDLImplementation/Pages/FINAL_PhaseII_WIPDocument_Main.aspx, October 2014.

Rees, Gwendolen, Alyssa Cultice, James Pease, Darrell Bosch and Kevin Boyle (2014). “Irrigation Systems and Practices in Mid-Atlantic Nurseries”. Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, Virginia Tech. Unpublished manuscript.

Williams-Woodward, Jean (ed., n.d.). “2010 Georgia Plant Disease Loss Estimates”. University of Georgia Cooperative Extension Annual Publication 102-3, retrieved from http://extension.uga.edu/publications/files/pdf/AP%20102-3_1.PDF, December 2013.

Horne, Ralph (2009). “Limits to Labels: The Role of Eco-labels in the Assessment of Product Sustainability and Routes to Sustainable Consumption”. International Journal of Consumer Studies 33(2): 175-182.

Yue, Chengyan, Jennifer Dennis, Bridget Behe, Charles Hall, Benjamin Campbell, and Roberto Lopez (2011). “Investigating Consumer Preference for Organic, Local, or Sustainable Plants.” HortScience 46(4): 610-615.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Program (n.d.). National Organic Program. Retrieved from http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/nop, June 2014.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service (February 2012). 2008 Organic Production Survey. Retrieved from http://www.agcensus.usda.gov/Publications/2007/Online_Highlights/Organics/, June 2014.

Hartter, David (2012). “Understanding Consumers’ Ornamental Plant Preferences for Disease-free and Water Conservation Labels.” M.S. thesis, Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, Virginia Tech. Print.