Staff — July 13, 2015

The significance of green roofs in urban areas has steadily increased over the past 20 years. In the United States, as well as worldwide, green roofs have become vital components of new construction on a broad variety of buildings, from municipal to commercial and industrial to residential. The benefits of green roofs are measured in environmental, economic and aesthetic or cultural ways. In its simplest form, a green roof may contain a sampling of sedums or other hardy succulents; whereas, many modern green roofs have increased the range and diversity of plants being grown by installing deeper growing medium and changing the way green roofs are utilized or experienced. Whether strictly utilitarian or highly specialized and ornamental, green roofs have a variety of benefits over a traditional roof.

When choosing plants for green roofs it is important to understand that a green roof is not the equivalent of a typical landscape elevated to the top of a building; therefore, appropriate consideration must be given to a plant’s growth habit, native ecosystem and cultural needs, to name a few factors. Many common garden plants will not survive on a green roof. In Green Roof Plants, Ed Snodgrass succinctly describes the ideal traits for a good green roof plant: “The most successful green roof plants are low-growing, shallow-rooted perennial plants that are heat, cold, sun, wind, drought, salt, insect and disease tolerant. Green roof plants should also have a long life expectancy or the ability to self-propagate, and they should require minimal nutrients and maintenance.” Needless to say, selecting the right plants for green roofs is anything but simple.

Photo Courtesy of iStock | JoolsBerlin.

The Chicago Botanic Garden Green Roof Gardens

In September 2009, the Chicago Botanic Garden opened its Daniel F. and Ada L. Rice Plant Conservation Science Center, a 38,000-square-foot LEED Gold-rated research and laboratory facility. Atop the Center is a 16,000-square-foot green roof, divided into two 8,000 square foot gardens, which display a variety of North American native plants and exotic plants from around the world. The green roof is both a living laboratory and a beautifully designed garden, with the two-fold purpose of displaying the best plants for green roofs and trialing untested plants for their adaptability to this challenging environment. The ultimate goal of the trial is to develop a diverse and extensive list of recommended plants for green roof culture. Greater plant diversity supports the aesthetic design of a green roof as well as creating a habitat for a variety of beneficial pollinators and other wildlife.

Photo courtesy of iStock | AlpamayoPhoto

Performance report

Between 2010 and 2014, 216 herbaceous and woodytaxa were evaluated in the green roof gardens; 129 taxa on the north roof and 87 taxa on the south roof. Data collection for the 156 taxa planted in August 2009 commenced in April 2010; 60 additional taxa started their trial in June 2011. A combined total of 41,561 individual plants were planted on the green roof in 2009 and 2011.

All plants were evaluated for their 1) cultural adaptability to the growing medium and environmental conditions on the green roof; 2) disease and pest problems; 3) winter hardiness or survivability; and 4) ornamental qualities associated with flowers, foliage and plant habit. In addition, plants were monitored for reseeding and weediness. Final performance ratings are based on plant health and vigor, survivability and longevity, habit quality and flower production, and winter hardiness during the evaluation period.

Nine taxa received five-star excellent ratings for their overall performance and survivability, including Antennaria dioica, Calamintha nepeta ssp. nepeta, Juniperus chinensis var. sargentii ‘Viridis’, Phlox subulata ‘Apple Blossom’, Phlox subulata ‘Emerald Snow’, Phlox subulata ‘Snowflake’, Rhus aromatica ‘Gro-Low’, Sporobolus heterolepis and Sporobolus heterolepis ‘Tara’. Top-rated plants consistently displayed good vigor and robust habits, superior ornamental qualities, disease resistance, heat and drought tolerance, and winter hardiness/survivability throughout the evaluation period. Additionally, 69 taxa received four-star good ratings for their strong performances.up-on-the-roof2

Early success for a portion of the taxa was evident by the end of the first full growing season in 2010.

Some taxa were consistently healthy but either slower to establish, slow to increase in size, and/or more affected by environmental conditions; however, by the end of the trial all of these taxa were good performers. Amorpha nana took five years to become a substantial size, although it remained irregular in habit. Asclepias tuberosa was very slow-growing; Baptisia alba var. alba was few-stemmed and open until the fifth season; Campanula rotundifolia was slow to bulk up until the third year; Coreopsis verticillata ‘Zagreb’ always had a loose habit. Eryngium yuccifolium was very slow to gain size; Fragaria virginiana was slow to begin spreading and its stolons were continually damaged during hot, droughty periods. Galium verum was not vigorous until the third season, except for its seedlings; Heuchera micrantha ‘Palace Purple’ grew well but off-colored dramatically in hot weather. Iris tectorum grew best in the shadier section of the bed; Lespedeza capitata was spindly for a couple of years. Liatris ligulistylis was slow to bulk up, often only single-stemmed; Oligoneuron album was fairly static until the third year when it began to reseed widely and the seedlings were more vigorous than the original plants.

Perovskia atriplicifolia was a bit loose in habit; Petrorhagia saxifraga ‘Rosea’ was healthiest interplanted with Phlox subulata ‘Emerald Blue’, whereas it lacked vigor on its own. Potentilla fruticosa was rarely bushy, being loose and uneven in habit; Pycnanthemum virginianum remained loose and often single-stemmed. Salvia ×sylvestris ‘East Friesland’ had a tight habit but never gained any size; Symhyotrichum ericoides ‘Snow Flurry’ stayed prostrate and never developed arching stems like it does in a garden. Symphyotrichum sericeum had an open to spindly habit; Talinum calycinum was slow to establish until it began to reseed; Thymus praecox ‘Coccineus’ did not become vigorous until the third year; and Tradescantia tharpii was slow to increase in size. Oenothera fruticosa ‘Fireworks’ and Oenothera macrocarpa were strong performers for three years but unexpectedly began to decline and die out in 2013.

Monitoring heat and drought

Environmental conditions, especially excessive heat and drought, were closely monitored to determine how they affected the health, vigor and survivability of the plants. Together or alone, heat and drought resulted in weakened plant health, partial vegetative loss, premature dormancy, and/or death. In many instances, plants weakened by environmental conditions during the growing season subsequently died in winter.

At the outset of the trial it was decided that irrigation beyond establishment would be restricted unless deemed necessary to ensure the survival of the green roof plantings. Between 2010 and 2014, irrigation was provided three times during periods of extreme heat and drought; the green roofs were irrigated once in July 2011, June 2012, and July 2013 for 30 minutes each time. All plants were impacted by drought in varying degrees at some time each summer, but plants growing in four inches of media were generally most affected and showed signs of drought-stress first.

Regardless of growing depth, Geum triflorum appeared to be the best indicator plant for drought, always being the first to show signs of heat- and drought-stress. Drought was never severe enough for Geum triflorum to go dormant or for more than a few plants to die, and health and vigor improved quickly once the droughty period was over. The leaves of Echinacea pallida, Monarda fistulosa, Potentilla arguta, Pycnanthemum virginianum, Rudbeckia hirta, Symphyotrichum novae-angliae and S. oblongifolium withered from the bottom up during hot, dry weather; the more severe the drought, the greater the leaf loss. Aquilegia canadensis went dormant in the hottest periods, and Viola sagittata stalled during droughty periods but rebloomed once moisture was available.

Andropogon gerardii and Bouteloua curtipendula seemed to be adaptable to dry conditions, but most of their lower leaves turned brown; Bouteloua curtipendula in four inches generally lacked vigor and some plant losses were noted in droughty periods. Conversely, Koeleria glauca, K. macrantha, Sporobolus heterolepis, and S. heterolepis ‘Tara’ off-colored the least during unfavorable conditions; however, Sporobolus heterolepis and ‘Tara’ showed earlier fall color following droughty periods. Summer dormancy of foliage was observed on Allium cernuum, Anemone caroliniana, Pulsatilla patens, Tradescantia ohiensis, and T. tharpii.

Penstemon digitalis established quickly and remained relatively robust throughout the study.Photo courtesy of  iStock | gardendata

iStock | gardendata

Other microclimates and conditions

A number of unique microclimates were observed on the green roofs, such as intermittent shade, localized incidental moisture, mechanical damage and increased fertility. The green roof gardens received full sun throughout the year except for an area along the southern edge of the north roof where the shadow from the atrium clerestory created some shade. The shadow was at its narrowest in mid- to late June, when only a few inches of shade was provided, and up to four feet wide when the sun was lower in the sky.

A few taxa were specifically sited to take advantage of the shade – Hosta ‘Cracker Crumbs’, Hosta lancifolia, Pachysandra procumbens, and Sedum ternatum ‘Larenim Park’. Shade encroached on a number of other taxa at various times in the growing season, resulting in a portion of the shaded plants being larger and lusher than their counterparts in full sun. In these cases, plant size differences ranged from slight to significant for the following taxa: Calamagrostis brachytricha, Calamintha nepeta ssp. nepeta, Gypsophila repens ‘Roseum’, Hosta ‘Cracker Crumbs’, H. lancifolia, Koeleria glauca, Perovskia atriplicifolia, Prunella grandiflora, Sedum ternatum ‘Larenim Park’, Sesleria caerulea, and Solidago ‘Wichita Mountains’.

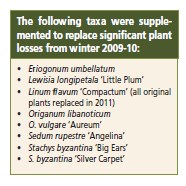

Conversely, a few of the taxa that received intermittent shade had plants that were smaller, looser and less vigorous in the shade than in the sunny areas, including Antennaria dioica, Eriogonum umbellatum, Lavandula angustifolia ‘Hidcote’, Linum flavum ‘Compactum’, Scutellaria alpina and Sempervivum ‘Le Clair’s Form’.

Lupinus perennis and Asclepias tuberosa were the only two taxa that died out completely in the first winter of 2009-10. In both instances, the original plants were weak when planted, and while many did not survive transplanting, the remaining plants succumbed to winter conditions. Both taxa were replanted in May 2011, and although most of the Asclepias tuberosa survived the replanting, none of the Lupinus perennis survived for more than a few weeks.

Some taxa were not well-suited to the environment and growing conditions on the green roofs, resulting in the gradual to rapid decline of plant health and eventual death before the end of the trial. Generally, these taxa lacked vigor or remained small, and in many cases, gradually died out over successive winters. The 30 taxa that did not complete the trial are noted in the full report.

Pest threats

Diseases and pests were fairly insignificant considering the variety of taxa and the sheer number of plants on the green roof. Powdery mildew, rust, leaf spot, phomopsis blight, aphids and lace bugs were the only problems observed. Minor powdery mildew was observed in multiple years on Monarda fistulosa, Penstemon digitalis, P. hirsutus, Symphyotrichum novae-angliae and S. oolentangiense. Only penstemons were troubled by foliar rust, with varying infection rates noted on Penstemon digitalis (minor), P. digitalis ‘Husker Red’ (severe), P. grandiflorus (moderate), P. grandiflorus ‘Prairie Snow’ (minor), P. hirsutus (minor to moderate), and P. hirsutus ‘Pygmaeus’ (minor).

A variety of plants were affected by bacterial or fungal leaf spotting including Fragaria virginiana, Hosta lancifolia, Potentilla arguta, Rudbeckia fulgida and Symphyotrichum novae-angliae. Juniperus horizontalis ‘Wiltonii’ was periodically troubled by phomopsis tip blight (Phomopsis juniperovora), but J. chinensis var. sargentii ‘Viridis’ was not. Spider mites were an occasional pest on Asclepias tuberosa, ranging from insignificant to severe infestations depending on the year. Chrysanthemum lace bug (Corythucha marmorata) attacks a variety of ornamental plants in the Aster family, such as chrysanthemums, asters, goldenrods, sunflowers and black-eyed susans, and was by far the most significant pest issue for Ratibida pinnata, Solidago rigida, Symphyotrichum ericoides, S. novae-angliae and S. oolentangiense. Infestations were typically severe, resulting in sickly foliage and weakened health.

Photo courtesy of Chicago Botanic Garden

Winter loss

Data collection began in April 2010 with an assessment of plant losses during the first winter of 2009-10. Of the original 35,988 plants planted in 2009, approximately 25 percent died during the first winter. In subsequent years, winter losses were never as great as the first winter; winter losses in later years were more commonly associated with weakened plant health due to environmental causes such as drought-stress rather than cold hardiness. In the spring of 2011, plants were added to several winter-decimated plots on the north green roof.

Snow and ice build-up was typically noted along the shaded edge of the north roof for several weeks longer in the spring than in other sections of the green roof; up to six feet into the bed could be covered. This phenomenon caused plants in this area to develop much later than plants growing just feet away. In addition, frost heaving and winter-desiccation were consistent problems for Armeria maritima ‘Alba’, A. maritima ‘Rubrifolia’, Aster oharai, Erigeron caespitosa, E. scopulinus, Penstemon grandiflorus and P. grandiflorus ‘Prairie Snow’. In some years, Heuchera richardsonii and H. micrantha ‘Palace Purple’ were affected to a lesser degree.

Adding color

Like any perennial garden, floral displays are vital on green roofs, too. An assessment of floral traits includes flower color, flower size, bloom period and flower production. Many taxa had exceptional floral displays, which enhanced the ornamental aspect of the green roof in spring, summer and fall. Early bloomers such as Viola sagittata, Antennaria dioica, Geum triflorum, Dianthus gratianopolitanus ‘Firewitch’, Phlox bifida, Tetraneuris herbacea, Tradescantia tharpii and cultivars of moss phlox (Phlox subulata), brought the green roof to life beginning in late April and early May.

Summer-flowering perennials provided the longest bloom periods, from June through August. Among the best shows of the summer-flowering taxa were Agastache foeniculum, Amorpha canescens, Bouteloua curtipendula, Calamintha nepeta ssp. nepeta, Coreopsis lanceolata, Dalea candida, D. purpurea, D. villosa, Koeleria glauca, K. macrantha, Penstemon digitalis, P. hirsutus and P. hirsutus ‘Pygmaeus’.

A variety of grasses added greatly to the late season show along with perennials such as Helianthus mollis, Hosta lancifolia, Hylotelephium ‘Rosy Glow’, Lespedeza capitata, Liatris ligulistylis, Salvia azurea var. grandiflora, Solidago rigida and Solidago ‘Wichita Mountains’.

Self-perpetuation

Plant survival on a green roof is due in part to its ability to perpetuate itself, whether by seed or by vegetative means such as rhizomes, stolons or suckers. Whether or not a plant was considered weedy depended on the rate and degree that it spread. None of the vegetative-spreaders in the trial were considered weedy or overly troublesome, at least in the way they were used here. In fact, a number of rhizomatous species were wide-spreading but did not form dense plantings. Artemisia ludoviciana var. albula ‘Silver King’ had a loose rhizomatous habit that worked well mixed with Dianthus gratianopolitanus ‘Firewitch’, where its silvery foliage created a nice contrast but it did not out-compete the dianthus.

Helianthus mollis also had a loose rhizomatous habit, forming a plot of single-stemmed to somewhat bushy plants; its potential to be too wide-spreading and potentially troublesome was noted. Rather than forming discrete clumps, Monarda fistulosa remained loosely stoloniferous. Fragaria viriginiana displayed a robust stoloniferous habit early in the season but the stolons were usually killed during periods of extreme heat and drought. Conversely, Fragaria ‘Stickbolwi’ never formed stolons during the trial, so its effectiveness as a groundcover was limited. Rosa carolina had a suckering habit that formed a thicket between the original plants, but as of 2014 the offshoots had not become problematic to nearby plantings.

Weediness is a nuisance on any green roof, but on a managed roof reseeding or spreading can be kept in check. However, on an unmanaged green roof, the proliferation of one or more species can overrun the roof, smothering or  out-competing desirable plants and decreasing the diversity of the planting.

out-competing desirable plants and decreasing the diversity of the planting.

Along with observing how prolifically and quickly a plant spread by seed, we also observed the pattern of dispersion or movement on the green roof. Plants were regularly monitored for seedling production to determine the degree of aggressiveness or weediness.

Despite heavy seed production on all of these taxa, the most aggressively weedy and/or wide-spreading of these species were Chamaecrista fasciculata, Hieraceum spilophaeum ‘Leopard’, Koeleria glauca, K. macrantha and Oligoneuron album.

Koeleria glauca and K. macrantha were grown on different roofs but acted in the same way by filling any open space with seedlings. Chamaecrista fasciculata is an annual species that produced an abundance of lush seedlings each spring, most arising in the same location as the previous year but some seedlings came up several feet away. C. fasciculata was unique in that it did not spread far but its countless seedlings formed a dense mass that smothered all nearby plants.

Rudbeckia hirta is a short-lived perennial that effectively acted like an annual on the green roof. In fact, it was originally planted as a seasonal display for the opening of the green roofs in 2009, but perpetuated itself quite fruitfully during several years of the trial, dispersing widely across the green roof.

Artemisia caudata is a biennial that produces a rosette of basal leaves the first year and a flowering stem the second year before dying out. Although quite a prolific reseeder, the seedlings did not travel far from the original plants. Seedlings of Calamagrostis brachytricha were not an issue in the growing beds, but each spring an immeasurable number of seedlings blanketed the gravel path adjacent to the planting bed.

In a few cases, taxa planted on the north green roof were eventually observed on the south green roof, including Dianthus carthusianorum, Leucanthemum vulgare, Hieraceum spilophaeum ‘Leopard’ and Petrorhagia saxifraga ‘Rosea’. Talinum calycinum was the only taxon that was observed moving from the south to the north roof. Several herbaceous taxa were discovered on the south roof, presumed to have seeded in rather than arriving with the original plants, including Veronica spicata, Lobelia spicata and Coreopsis tripteris. In addition, a number of woody plants seeded in at various times over the course of the trial, including Salix sp., Alnus hirsuta, Crataegus phaenopyrum, Acer negundo, Populus deltoides and Fraxinus pennsylvanica. Woody plants were generally not suited to the growing conditions and did not thrive.

More of this report, including site and study specifics and information on those plants that did not fare well, can be viewed online at http://www.amerinursery.com.

Cover Photo courtesy of Chicago Botanic Garden