Mary Meyer — September 1, 2014

Finding plants that tolerate the occasional soaking—or a short period of standing water—can be tricky. But there are several ornamental grass varieties that are up to the challenge.

Finding plants that tolerate the occasional soaking—or a short period of standing water—can be tricky. But there are several ornamental grass varieties that are up to the challenge.

Click image to enlarge.

Extreme weather events appear to be the new normal, with many storms producing heavy downpours that can cause erosion or leave standing water in low areas. Although drought has been the focus for California and much of central U. S. recently, wet sites can be just as challenging, hosting conditions of too much moisture that can reduce or eliminate soil air and oxygen, both of which are essential for root survival and growth. Dealing with rain events that leave several inches of water in a brief period of time requires close attention to how water moves—or not—on a given site.

Proper plant selection becomes critical in sites whose soil moisture may vary widely throughout the season. Watching water accumulate and move during rain can be very insightful for plant selection and placement.

Click image to enlarge.

Carex elata ‘Aurea’ (Bowles’ golden sedge). Top of page, Acorus calamus ‘Variegatus’ (variegated sweet flag)

All photos: Courtesy of Mary Hockenberry Meyer

Consider grasses

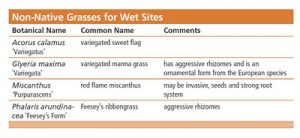

Grasses are tough plants that can be counted on to perform in difficult sites. Wet or dry, there are grasses that grow naturally in these extreme conditions. The fibrous roots of bunch grasses and the tough, woody rhizomes of spreading grasses are excellent at stabilizing soil and preventing erosion, whether on steep slopes or on lakeshores and stream banks.

Grasses tolerate seasonal variations in soil moisture, and some are quite forgiving of standing water for 24 hours. In determining what grass can fit your needs, study how water moves or accumulates on your site. Determine how long water stands in a specific location, or if it rarely leaves. Few, but some, grasses can tolerate standing water for more than 24 hours.

Knowing your soil type is also helpful. Sites with sandy soil that drains well, but floods occasionally, create a challenge because plants may end up with extremely wet or dry conditions.

The right choice

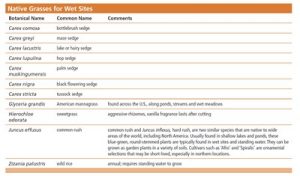

Which grass will grow and thrive in wet sites? Actually, quite a few! Here are a few of my favorites, and a list of additional species, along with comments on growth and management.

Calamagrostis canadensis (bluejoint or bluejoint reedgrass) is our U.S. native counterpart to Karl Foerster reedgrass, one of the most popular grasses sold today. Native to most of the U.S. except the southeastern states, bluejoint is found in marshes, wet places, open woods and meadows. It prefers moist soils, has some shade tolerance, and grows to 3 to 5 feet in height, with flowers in July.

Bluejoint can self-sow and its aggressive rhizomes require management in a garden setting, but it can be an asset along ponds or lakeshores. It’s hardy to Zone 3.

Click image to enlarge.

Carex elata ‘Aurea’ (Bowles’ golden sedge)

Carex elata ‘Aurea’ (Bowles’ golden sedge) is a bright yellow bunch sedge that can be grown in standing water, wet sites or in heavy, clay soil. Dry locations will produce shorter plants with less vigor. The brilliant yellow foliage stays attractive and bright all summer. Inconspicuous seedheads appear in late spring but are not noticeable.

Combine this plant with blue Siberian iris for a nice contrast. Native to Europe and at one time hard to find in the trade, Bowles’ golden sedge is hardy to Zone 4. It is slow-growing and easy to care for, and plants grow quickly in early spring reaching a height of 15 to 24 inches.

Click image to enlarge.

Carex muskingumensis (palm sedge)

Carex muskingumensis (palm sedge) is a bushy, tough sedge that tolerates most soil and light conditions. Bright chartreuse in sun, darker green in shade, this 2- to 3-foot sedge has many stems, all with conspicuous three-leaf ranking, making it an easy sedge to distinguish from true grasses. Named for the Muskingum River in Ohio, palm sedge is found growing in low woods, wet meadows and floodplain forests. Tan seedheads are more numerous in sunny conditions; they readily self-seed, making larger colonies of plants.

Palm sedge is a bunch sedge with no rhizomes, but robust stout roots. Hardy in zones 4 to 9, it’s a good choice for tough sites, and even dry shade can be a productive site for palm sedge. The best ornamental form is ‘Oehme’, a 2-foot-tall, light green or yellow striped, less vigorous form named after the landscape designer Wolfgang Oehme. ‘Little Midge’ is a diminutive form, growing less than 1 foot in height, with very fine textured, three-leaf ranks; it’s so small that it may be lost in the garden, so it’s best used in a close, upfront setting. ‘Ice Fountains’ has white stripes with lax foliage, grows to 2 feet with much less vigor, but the bright foliage lights up a shady site in moist or wet soils.

Click image to enlarge.

Click image to enlarge.

Chasmanthium latifolium (wood oats)

Click image to enlarge.

Chasmanthium latifolium (wood oats) in the fall

Showy Chasmanthium latifolium (wood oats), is native to Pennsylvania south to Georgia and west to Texas, Oklahoma and Illinois. The short, wide leaf blades along with the distinctive flat seedheads make wood oats easy to identify. Flowers are showy from midsummer through fall and early winter. If cut early, this is an excellent cut flower; as the heads age, however, they easily shatter and can readily self-sow. Wood oats grows best in rich woods and moist soils, along streams and rivers where it can reach 2 to 5 feet in height.

Originally wood oats was classified as Uniola, the genus for our native seaoats, a wonderful soil binder along the eastern seashore. Wood oats, or northern seaoats, is hardy to Zone 4; plants can be short-lived that far north, however, but will likely self-seed. C. latifolium may be weedy with seedlings in warmer climates.

Click image to enlarge.

Panicum virgatum ‘Dallas Blues’ (‘Dallas Blues’ switchgrass)

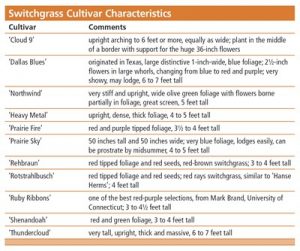

Native to most states except those in the Far West and Northwest, Panicum virgatum (switchgrass) tolerates a wide variety of soils. Switchgrass is a common plant in wet ditches and along roadsides. More than 25 cultivars have been selected from native populations and vary widely in height, foliage and flower color, and plant form. Regional selections are best to use for very warm or cold climates, such as Florida, Maine or Minnesota. Most cultivars are hardy in zones 4 to 9.

Seed propagation will result in variation, but is essential for restoration work where local biotypes will perform well in a specific geographic region. Cultivars may be more desirable in a garden or landscape setting, where a uniform consistent plant form is needed. Switchgrass is a bunch grass with slowly spreading rhizomes. Reseeding is common on moist fertile soils.

Click image to enlarge.

Spartina pectinata (prairie cordgrass)

Spartina pectinata (prairie cordgrass) is native from Oregon to Maine and south to North Carolina and New Mexico; it is hardy in zones 4 to 9. Its stout, woody rhizomes are perfect for maintaining lakeshores and minimizing erosion. It prefers wet prairie sites or moist soil in open sun conditions and easily grows in clay soils. The long, straplike leaves and coarse green flowers grow from 5 to 7 feet in height.

Prairie cordgrass is not a neat and tidy typical garden plant, but is a valuable native grass that will hold its own against difficult sites and a wide variety of soil types. It is best used with other large prairie natives, such as cup plant, sunflowers and asters. The ornamental form, ‘Aureo-Marginata’, variegated cordgrass, has a yellow stripe along the leaf and is very similar to the species in habit and growth.

Click image to enlarge.

Wet sites can be just the location for a few tough grasses and sedges like these. Minimal care is involved annually; simply cut back the tops in late winter or early spring. No pesticides or special fertilizer are needed to grow these sustainable grasses.

Click image to enlarge.

Mary Hockenberry Meyer is Professor in the Department of Horticultural Science and Extension Horticulturist at the University of Minnesota, where she specializes in ornamental grass research. She is the 2013-2014 President of the American Society for Horticultural Science. Dr. Meyer can be reached at [email protected].