John Ball — October 1, 2014

Substitutions in landscape plans can be a source of confusion and frustration, unless it’s clearly stated what the policy is. The best place to start is to understand why a plant was specified.

Click image to enlarge.

Flower color and time of bloom can be important considerations when specifying a particular plant. But are those qualities made clear?

All photos courtesy of John Ball unless otherwise noted. Clouds: Getty Images/iStockphoto

“May I have breakfast potatoes instead of hash browns and a muffin rather than toast?” These questions are commonly over-heard when ordering Sunday breakfast. Everyone seems to want to substitute at least one item for something else on the menu; it’s almost an American tradition!

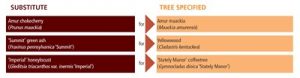

This game of substitutions is also becoming very common in the landscape industry. I just reviewed a plan for an architectural firm where the landscape contractor identified substitutes for a number of tree species on the project. Below are some of the requested substitutions, as well as the tree specified on the material list.

Click image to enlarge.

How appropriate are these substitutions? Some may seem like a stretch, but you cannot really be certain (except for the green ash; most likely the contractor had trees to dispose of since emerald ash borer has made ash planting almost taboo). Let’s take a look: It appears the only thing that the Amur chokecherry and Amur maackia have in common is the word “Amur” in their name; they do not have the same flowering or fruiting characteristics, although both have attractive winter bark. Perhaps the critical design feature was the winter appearance, not late summer flowering. But who knows?

This is one of the difficulties contractors face when suggesting substitutes for unavailable plants. Too often the contractor is left in the dark about the function of a particular plant and when a substitute is needed, the suggestion is met with disbelief by the designer. “Did they just pick something out of a hat?” is a remark frequently expressed by a frustrated designer who is enduring yet another request to substitute one plant for another. Contractors are not mind readers, and they should not have to guess at the particular purpose of a species or cultivar in the landscape. Plants are not just green blobs randomly placed across the landscape. Each should be an integral part of the design, its combination of form, texture and color providing an important function. I look at the whole landscape as a big jigsaw puzzle where every piece has a unique fit, and the loss of any piece means the landscape may not be complete. Hopefully the designer had a reason for putting the plant in the design; there should be one or more features of the plants that were important pieces in the landscape puzzle. A substituted plant may not have the desired features and be the piece that does not fit the puzzle.

Avoid the frustration

Difficulties with substitutions can be avoided by stating “no substitutions accepted” on the plant material list, but this practice creates a lot of new headaches. The “no substitutions” policy can add to the cost of a project. Installation bids for these “no substitution” projects may be higher to cover the cost of obtaining plants with limited availability.

The requirement of “no substitutions” may also have little impact on the final project anyway, as a change in plant availability between when the project was bid and when the installation began may force a change in material regardless of the contract. Saying no can seem like an easy solution, but it usually just complicates the project. So what is a reasonable policy on substitution? The solution to finding appropriate substitutes involves two parties: the landscape architect or designer who created the particular plant material list, and the contractor who will be installing the project.

Click image to enlarge.

What does this Amur maacckia (Maackia amurensis) have in common with Amur chokecherry (Prunus maackia)? That’s a trick question, but the substitution has been suggested on landscape plans.

First, landscape architects and designers need to be realistic about selecting the materials they place in their projects. There is not much to be gained, except frustration, in specifying material that is not available in the numbers or sizes desired. The “flavor-of-the-month” approach to design should be avoided. What do I mean by that? It’s the temptation to specify new cultivars merely for the reason that they are new, with little thought given as to their availability.

I once bid a project that required a specific tree cultivar, one relatively new to the trade and nearly impossible to obtain at the size requested. Our company lost the bid, and one factor was that our cost of obtaining this cultivar at the specified size was quite high due to the transportation costs of getting these trees from a distant nursery to the site. I drove by the landscape site a couple of months later, curious to see the cultivar, and I noticed that the specified cultivar had not been installed—not even a tree of the same species! When I called the designer, his comment was he had not been aware of the cost and difficulty of acquiring the specific cultivar and they saved a lot of money with the substitution!

Click image to enlarge.

Amur chokecherry (Prunus maackia)

If a specific plant is specified, the landscape architect or designer should be aware of its availability at the requested size and the approximate cost. Several years ago I reviewed one design that indicated Prairie Expedition® elm (Ulmus americana ‘Lewis & Clark’) at 3-inch-caliper B&B. This American elm cultivar was relatively new at the time and still being grown to size in the field. Large caliper materials were limited, a fact that would have been apparent to the designer if he had just checked with a few wholesale nurseries.

If the plant is available, and at the desired size, then the landscape architect or designer should also have some idea of the cost—and if it is higher than typical for a plant of that size, perhaps due to limited availability, either find another species or cultivar or build the cost into the estimate. Do not reduce the task of fulfilling a plant material list to the equivalent of a horticultural scavenger hunt.

Further, do not specify plants if they are unobtainable, and definitely do not waste the contractor’s time by identifying plants that you will substitute if the cost is too high. Accepting any substitute—regardless of its dissimilarity to the plant specified—just makes a mockery of a plant material list. I recall working with one designer about whom contractors joked: Get his list, throw it away and find the same number of trees that were the cheapest. Then send those in as substitutes on the bid!

Click image to enlarge.

The flowers of Amur maackia bear little resemblance to those of Amur chokecherry, nor is the bloom time similar.

A general approach

A general policy of accepting substitutions makes sense. It allows for flexibility and can reduce costs and speed up the installation. But just stating, “substitutions may be approved,” does not provide much guidance to the contractor. Too often it becomes a guessing game in which the contractor, faced with needing a substitute, provides a list to the designer. That list is either accepted or rejected and, if rejected, it’s often without a stated reason.

![]()

Click image to enlarge.

It would be far more helpful in the substitution process if the contractors had some appreciation of the function of the particular plant in the design; what puzzle piece did it provide? Was it selected for its shade? Or was there an aesthetic characteristic that drove the selection —the form, flower color and timing, or autumn foliage color? Perhaps the site characteristics were the determining, and limiting, factors; were alkalinity, compaction or other environmental conditions the keys to the selection? Allowing substitutes makes sense, but there has to be some guidance as to what constitutes an acceptable substitute.

Click image to enlarge.

The mature size and shape of a plant can be one of the important characteristics for which a plant is specified. Substitutions that don’t take this into account are sure to fail.

The landscape industry has numerous policies regarding other aspects of substitutions. Bid documents, for example, often state that requests for substitutions must be made in writing and at least 30 days before the projected planting date. Regarding the plants, however, we often say little about what makes an acceptable substitute. Too often, the contract simply states whether or not substitutions are accepted, or that substitution requires approval by the landscape architect or designer.

But what if the landscape material list was similar to the list below?

This approach provides some guidance to contractors as to what the designer is looking for—summer flowering and height—and what might be an acceptable substitute. Rarely is one specific plant critical to a design, but one or more characteristics of that plant may be.

The list of acceptable substitutes need not be long or exclusive, but it can be invaluable in guiding the contractor through the substitution process. Letting contractors know the key factor—say, mid-summer flowering time in the example of the Amur maackia—and the range of acceptable time—such as flowering from mid- to late summer—helps avoid the problem of a spring-flowering Amur chokecherry being proposed as a substitute. If the contractor is not able to obtain the requested plant, yet finds a substitute that fulfills the key requirement, there’s a good chance the substitute will be accepted.

Contractors also have a responsibility in the substitution process. The first responsibility, of course, is to acquire the designer’s preferred plant. But failing that, the contractor must adhere to the intent of the design by obtaining an acceptable substitute, and not suggest a plant merely because it is easy to find or it was already on hand. The ornamental landscape is being overloaded with Autumn Blaze® maples, ‘Stella d’Oro’ daylilies and ‘Karl Foerster’ feather reed grass – all fine plants, but they are quickly becoming the universal substitutes for every tree, flower or grass placed in the landscape.

Substitutions will continue to be a part of the landscaping process. But availability can be volatile, often dramatically changing from the time of the design and creation of the plant list to the installation. A policy of “no substitution” is not often realistic; however, neither is accepting any plant as a substitute. Substitutions at breakfast are great, but in landscapes, they should be limited and appropriate.

John Ball is Professor of Forestry at South Dakota State University, Brookings. He can be reached at [email protected].